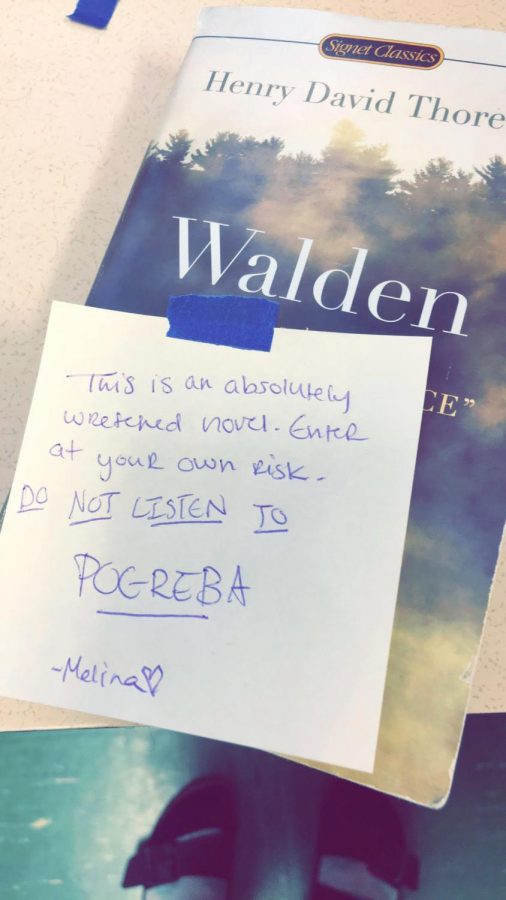

Thoreau-sted

A Letter to Pogreba

November 19, 2018

Henry David Thoreau is renowned as one of the most prominent figures in transcendentalism and philosophical literature. Born in 1817, Thoreau grew up in a thriving new era of intellectualism, and became an author mid 1840’s with his first work, Walden. It’s unfortunate that Walden could have been better written in three pages of a journal entry by any modern hippie today. That is, after all, what Thoreau seemed to be, a woodsy hipster of his time who seemed to think that it was something special to move:

about two miles from the village, half a mile from the nearest neighbor, and separated from the highway by a broad field; its bounding on the river, which the owner said protected it by its fogs from frosts in the spring, though that was nothing to me; the gray color and ruinous state of the house and barn, and the dilapidated fences, which put such an interval between me and the last occupant; the hollow and lichen-covered apple trees, gnawed by rabbits, showing what kind of neighbors I should have; but above all, the recollection I had of it from my earliest voyages up the river, when the house was concealed behind a dense grove of red maples, through which I heard the house-dog…(67-68)

I’ll stop there, but this excerpt makes another point; Thoreau is an unfortunate master of something that is despised by nearly every literary critic: the run-on sentence. The excerpt above is one sentence, and this is perhaps one that can be more easily understood. In many of his run-ons throughout Walden, Thoreau does nothing but ramble about the inner workings of nature and the realizations of the “youthful philosophers and experimentalists we are” (269). This makes his work confusing and hard to follow, not to mention boring and uneventful. Using a modern example, it’s similar to Tolkien’s drawn-out language in Lord of the Rings, except for the fact that Tolkien is much easier to follow (which is saying something). This makes Thoreau’s overall writing style a nuisance to read, and makes the content mind-numbingly boring.

On the topic of content, in fact, Walden isn’t strong either. Granted, I’m no Thoreau completist and Walden was his first novel, so perhaps there is room for improvement in his later works. He also did attend Harvard, which is an honorable accomplishment that shouldn’t be left out. Admittedly, what I have read in his writings about civil disobedience, as well as a select few poems, are quality work in which he does suggests something greater than the self. Walden, however, is simply too much. Unapologetically, no one tree deserves three pages of description, nor do a trail of ants. Nature is absolutely beautiful in its glory and pureness, but to talk about one bird in run-on sentences for five pages ruins the beauty of the moment. It’s almost as if Thoreau was trying to outdo his mentor, Ralph Waldo Emerson, by simply adding more adjectives to every single thing he saw. Thoreau is the knock-off album of Emerson’s original masterpieces; and it’s arguable that one of the only reasons Thoreau gained any status whatsoever was due to his association with an accomplished and well-written transcendentalist.

Thanks to all of this, Walden feels strained. The tone feels like the equivalent of a tweet about going to the gym: if you didn’t share and brag about it, then you didn’t go at all. If Thoreau had truly wanted to appreciate his environment in the way that he boasts about, he would have done it in 200 less pages.

This moves the topic to perhaps my least favorite part of Thoreau, which happens to be a huge element in Walden: his personality. As mentioned earlier, he lives no less than, “half a mile from the nearest neighbor.” To put this into context, half a mile is about the distance from Helena High to the McDonalds on Prospect, or about twenty minutes walking time according to Google Maps. He seems to have some sort of Western expansionist mindset, but not the determination to go more than twenty miles beyond his hometown of Concord, Massachusetts. Thoreau paints himself as some sort of mountaineer, but in reality, he’s just a wanna-be Montanan who thinks he’s special for doing something fairly common for his era. Plus, he’s not doing that well at it. The entire plot of Walden, transcendentalist interpretations aside, is Thoreau building a cabin (with three chairs, exciting!), looking at a pond, and very slowly planting a field of green beans. He believes that he’s an amazing farmer with some sort of natural talent. Take his words over mine, however: “I was more independent than any farmer at Concord, for I was not anchored to a house or a farm, but could follow the bent of my genius, which is a very crooked one, every moment.” Thoreau is so full of himself that he is impossible to take seriously which only adds to the ridiculousness of Walden.

From his constant run-on sentences to his arrogant and pretentious tone, Thoreau struggles to reach the standards that American literature set for everyone else, despite his supposed celebrity status in nature writing. He’s living proof that just because someone uses a lot of words, it doesn’t mean that they have anything interesting or meaningful to say. Everyone has such high hopes for Thoreau, and he does nothing but crush them under the weight of too many words. Ultimately, Thoreau is an overrated “intellectual” who uses glittering generalities to make himself sound better than he is, and Walden is so weighed down with its own ego it’s almost impossible to turn the pages.

*all citations are taken from the Signet Classics edition of Walden and Civil Disobedience