Did you know that by 1870, there were 648 Chinese immigrants living in Helena? And in Butte, from 1891-1894 the city received a wave of 841 Chinese immigrants?

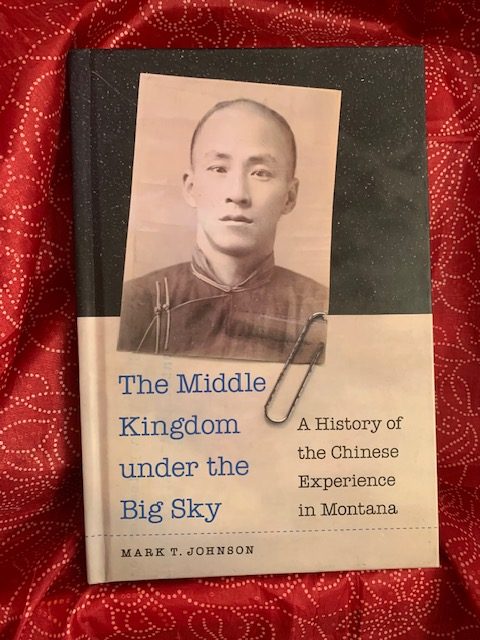

Among the countless gravesites that dart and scatter the Montana landscape, hidden among the tall, dry grasses are shrines and tombstones of immigrants whose work and dedication to this state have been largely forgotten. One of those resting places lies next to Forestvale Cemetery north of Helena. Mark T. Johnson, a professor, researcher, historian, and teacher, has been researching such sites, as well as historic documents, and has written a new book on the history of Chinese immigrants in Montana.

Mr. Johnson’s book, The Middle Kingdom under the Big Sky: A History of the Chinese Experience in Montana, published by the University of Nebraska Press, covers the full details, stories, and history of the Chinese immigrants that built up the state of Montana. Mr. Johnson recently visited The Nugget journalism class for an interview.

Many have forgotten or have never heard about the integral part Chinese immigrants played in daily life in the state of Montana. Their deeds are overshadowed by the Irishmen, the Scots, the Germans, and other such immigrants. However, Chinese immigrants were among the hardest working pioneers, shop owners, gardeners, and miners. They strived to earn acceptance as citizens and work toward their dreams—earning a living for their families and sending funds to their relatives, and a better governed and reformed Chinese Empire. While many immigrants were treated harshly, the Chinese suffered even harsher conditions due to their differences compared to their European counterparts.

Some of the most interesting stories of Chinese immigrants were centered in Butte and here in Helena, two of the largest hubs for all immigrants in Montana. From 1899 to 1906, the Chinese Empire Reform Association saw an opportunity to break open a steppingstone to a better governed and politically modernized Chinese Empire. They focused their efforts all over North America, but especially here in Montana. This group advocated for Chinese immigrants of Montana to fight back against what was known as the Geary Act during the mid-1890s, which sought to expel the Chinese from the U.S.

The Reform Association encouraged Chinese Montanans to become active in changing the Empire. The head of this empowering movement, Kang Youwei, advocated for both his people at home and abroad, often calling out the more conservative Dowager Empress Cixi and the Imperial party for their faults and for being outdated. According to Johnson, many Chinese Montanans joined the Reform Association because “the Chinese state was weak, and it couldn’t stand up for its citizens [in the United States]. The guys here who joined those Reform Associations knew that if China was stronger, their situation here would be strengthened.”

From her ascension to the Chinese throne in 1835, Chinese Dowager Empress Cixi ruled China the way she sought fit. Johnson said that after reformers attempted to change the Chinese government, she “retook control and executed every one of the reformers she could get her hands on.” Her policies included major military reforms and numerous conservative practices.

The Reform Association certainly made progress in Butte, but here in Helena, it was much more difficult. Chinese people in Helena were less interested in the reform because they had prospered more and were focused on their own self-improvement. They seemed to have no care for the reformist ideals of the Association. Nevertheless, the seeds of reform for China were planted here in Montana by Youwei and the Reform Association.

Members of the Association took their political and military duties very seriously. Often, they would be seen conducting military drills, doing target practice, and developing strategies to one day return to China to face off against the Dowager Empress and the Guangxu Emperor.

While the ideals of a reformed Chinese Empire were on the hearts and minds of the Chinese immigrants, home life was also important. There were many industries in which the Chinese immigrants earned a living, but one of the biggest forms of work was Montana’s most famous: mining. From the time that precious metals were found in the 1860s by veterans of the American Civil War, groups of men flocked to Montana to harvest these riches. Englishmen, Irishmen, Scots, and many more immigrants started racing to Montana to join in on the fun.

They had one thing in common: a hatred towards the new Chinese pioneers. They were constantly threatening violence against Chinese immigrants. “Thankfully,” said Mr. Johnson, “in Montana there were not instances of major bloodshed against the Chinese . . . but what often was the tool against the Chinese in Montana were boycotts: trying to get white consumers to not purchase Chinese made goods.”

The other immigrants also often made very racist remarks. They said that the Chinese would never be citizens, that whatever they mined would go back to China, and that they were “horseleeches” feeding off good Montanan work. Much of the money Chinese workers earned did go back to China. As Mr. Johnson pointed out, “The area they came from was beset with floods and famines and earthquakes – it was horrible living conditions – so the money they earned here kept people in southern China alive.” Given these awful conditions, it’s understandable that homesick people would send money back to their families.

However, in 1872, the Montana Legislature banned the Chinese from the continuation of mining. But just like any Montanan, the Chinese would not give up. Soon these Chinese men and women began to set up essential shops to help the needs of incoming pioneers, albeit the businesses would be boycotted by the locals. The Chinese opened clothing shops, laundromats, restaurants, and provided general labor.

Then there’s the matter of the elusive vegetable gardens.

For generations, students here at Helena High School have often debated amongst themselves if this school is sinking, with rumors that it was built over a swamp or even a Chinese garden. Well, the idea that what was here before is causing the school to sink might not be wild speculation. Examples of Chinese vegetable gardens in Montana can be documented throughout the state. For example, in Bozeman there was an account of a Chinese man coming into town from one of these gardens at 6 A.M. to sell dewy vegetables. In 1883, in Beaverhead County, there was a news report made about one of these vegetable gardens that described it and its owner as “heathens” but praised both for being “surprisingly” better than the white agriculturists.

In recent years, HHS students and teachers have used these examples of Chinese gardens as a possible explanation for the school’s sinking state. For Helena’s case, there have been records of Chinese gardens here in Helena, according to Mr. Johnson, mainly in the downtown areas such as near Reeder’s Alley and out in the Helena Valley. Truthfully, not much is known about the exact vegetables that were grown and sold. Often accounts varied from mentioning cucumbers, string beans, and corn to cabbages, cauliflower, and radishes: most of these vegetables are not natively grown in the United States.

Mr. Johnson has attempted to confirm the existence of a Chinese garden that predated the building of Helena High; however, he has not seen evidence from documents at the time that that is actually the case.

“The references about this idea come from much later,” he wrote in an email. “I have tried to corroborate that with research into maps, newspapers, and more from before the construction of HHS, but have yet to find definitive proof that Chinese gardens were at the site.”

Now what does this mean for the students of HHS and for Helenans as a whole? Well, for one, this means there may have been gardens here on the Helena High School grounds, but great claims need great evidence. For now, the issue remains a mystery for the city of Helena and Helena High.

In later years, through World War II and the Cold War, the Chinese in Montana had to prove their loyalty to the United States again and again. Back on mainland China in WWII, Chinese people watched as a war with the Japanese tested the strength of the government and eventually led to its collapse with a communist government now known as The Peoples Republic of China take power and the older government fleeing to what is now Taiwan.

Because China was one of many other Asian countries that were under the thumb of the Japanese Empire, many in America viewed China and its people as spies who worked for the Japanese or confused the Chinese for Japanese. In response, these Chinese immigrants took up rifles, joined the American army, and died by the thousands for America as soldiers in World War II.

During the Cold War, the fear of Communism stretched to the United States, and the Chinese people were once again targeted, this time as suspected communists. Attacks during this period mirrored Montana’s earlier history with boycotting and violence.

Today, several businesses of Chinese immigrants have thrived and endured in Montana. In the city of Butte, the Pekin Noodle Parlor, a traditionally family-run Chinese restaurant, has been in operation since 1911. The artwork, culture and resting places of these extraordinary people still can be seen from the biggest cities to the smallest towns here in Montana. Still, their deeds are dwarfed and overshadowed by the focus on European immigrants.

So, the next time you visit a mine, or any mansion, or downtown restaurant, just remember that among the immigrants who worked and lived here in Montana, the Chinese did some of the hardest work to make our great state and home what it is today.